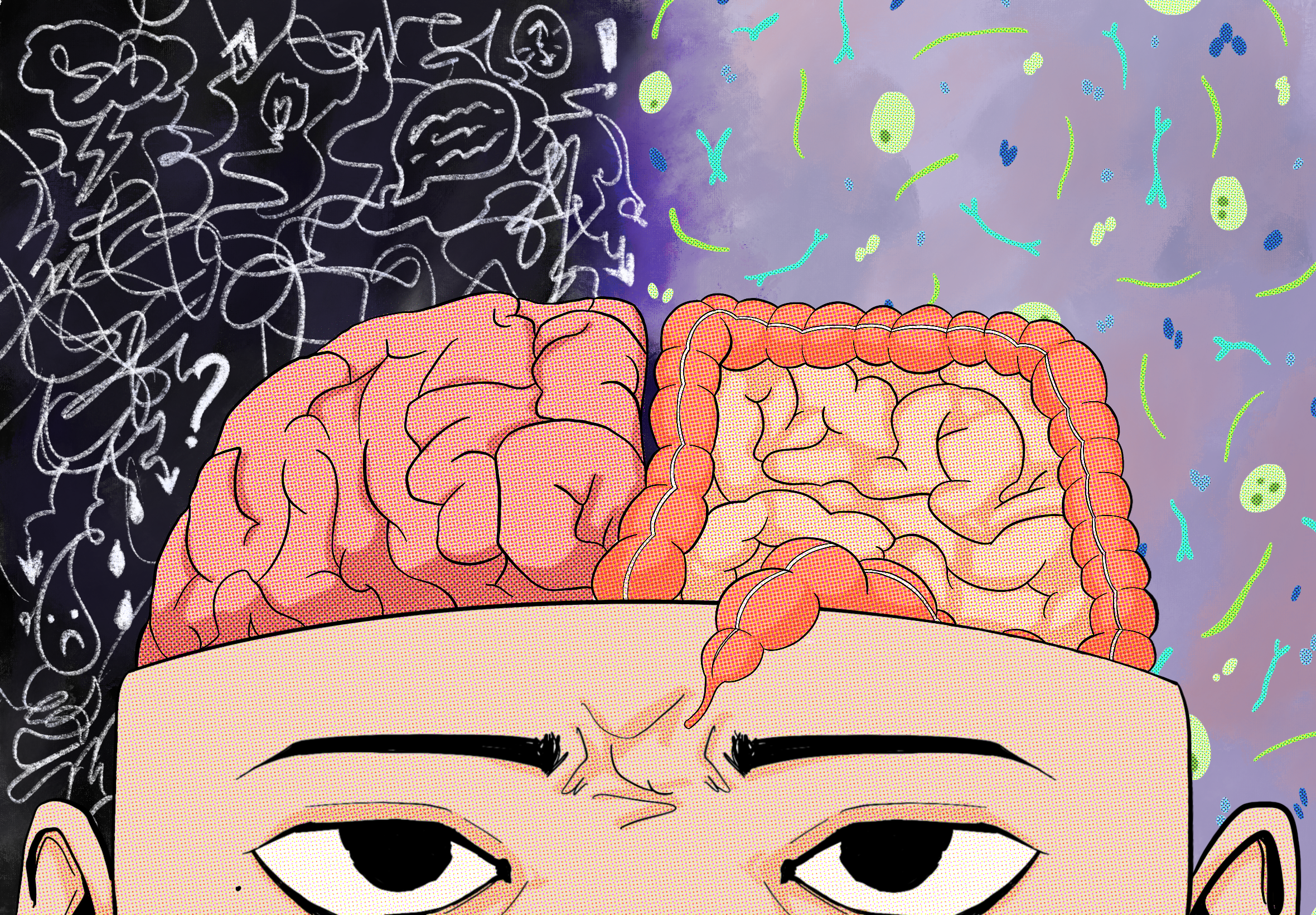

Our Microbiome’s Connection to Human Health

How does the gut microbiome play a role in conditions such as depression?

Written by: Sarah Chen | Edited by: Elle Scord | Graphic by: Janessa Techathamawong

Mental health is an increasingly prevalent topic in social media, news outlets, and everyday conversations. As pharmaceutical companies race to develop new drugs for depression and anxiety, and therapy companies urge people to prioritize their mental health, discussions of mental health have largely been framed through neurological and psychological lenses. However, new studies show that mental health may be linked to the gut as well. The gut microbiome, which is affected by the food we consume, is deeply connected to our mental health.

This connection is known as the microbiota-gut-brain axis, which includes the central nervous system (CNS), enteric nervous system (ENS), parts of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), gut microbiota, neuroimmune system, and neuroendocrine pathways. These different parts of the brain and gut constantly communicate with each other, sending important messages. A major route of this signaling is the vagus nerve, which has been linked to various mental health conditions, such as depression.

The gut microbiome is highly intertwined with the foods that we consume on a daily basis. For example, lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in probiotics, synbiotics, prebiotics, dairy products, and spices can increase protective microbiota in the gut. One study, from the University Complutense of Madrid, used Simpson’s diversity, a way of measuring species diversity in a location by looking at the number of species and the abundance of each species. The study found that individuals with anxiety had lower Simpson’s diversity of microbiota in their gut.

For depression, a study has found a link between decreased diversity and increased risk of depression. Another study analyzing data from several thousand individuals has found that there is a clear connection between Morganella morganii and major depressive disorder (MDD). Morganella morganii is also implicated in Type 2 Diabetes, which shows that the gut microbiome is a promising field of research for mental health. Prevotella, Klebsiella, Streptococcus, and Clostridium are all microorganisms found in higher amounts in patients with major depressive disorder, while Bacteroidetes was found in a lower amount.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a relatively new solution that can be used to treat patients living with depression, which scientists are continuously investigating. The technique involves transplanting the purified feces of one person to another, with the hopes of increasing the gut microbiome diversity. While for some, FMT has helped to alleviate symptoms and lead to a higher quality of life, FMT does not work on all patients, and some still take antidepressants.

Besides the link between the gut microbiome and mental conditions such as anxiety and depression, studies have elucidated a link between the gut microbiome’s diversity and stress management skills. A team of researchers, including UCLA neuroscientist Arpana Church, found that certain “BGM [brain-gut microbiome] markers distinguish the HR [high-resilience] group from the LR [low-resilience] group”. These markers included microorganisms with functions that protected gut health. The high resilience group was associated with lower depression, anxiety, neuroticism, and perceived stress.

It is clear that the connection between the gut microbiome and mental health should be further explored. Future research should aim to prioritize how gut microbiome diversity can be best preserved from generation to generation in industrial societies.

These articles are not intended to serve as medical advice. If you have specific medical concerns, please reach out to your provider.